What follows are selected excerpts from “Patronage and Reciprocity: The Context of Grace in the New Testament” written by David A. deSilva. The full document is linked above, and is well worth reading if you have the time. (it’s more than 4x longer than this article) If you don’t have the time, I hope my humble abridgement will broaden your understanding of Grace in the New Testament.

(NOTE: To enhance readability on the internet, I’ve added non-original headings to organize the content. I’ve also added some emphasis to his words in the form of red, bold, and underlining to highlight his main themes for ease of reading.)

What is Patronage?

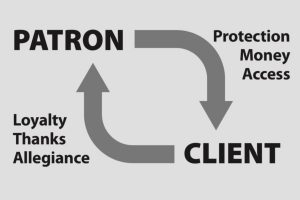

The term “patronage” refers to a system in which access to goods, positions, or services is enjoyed by means of personal relationships and the exchanging of “favors” rather than by impersonal and impartial systems of distribution.

Patronage is not strictly a Roman phenomenon, even though our richest discussions of the institution were written by Romans (Cicero in De officiis and Seneca in De beneficiis).

Where patronage occurs (often deridingly called nepotism: channeling opportunities to relations or personal friends), it is often done “under the table” and kept as quiet as possible.

The world of the authors and readers of the New Testament, however, was a world in which personal patronage was an essential means of acquiring access to goods, protection, or opportunities for employment and advancement. Not only was it essential – it was expected and publicized! The giving and receiving of favors was, according to a first-century participant, the “practice that constitutes the chief bond of human society” (Seneca, De beneficiis 1.4.2)

For everyday needs there was the market, in which buying and selling provided access to daily necessities; for anything outside of the ordinary, one sought out the person who possessed or controlled access to what one needed, and received what one needed as a “favor.”

The kinds of benefits sought from patrons depended on the need or desires of the petitioner: they might include plots of land or distributions of money to get started in business or to supply food after a crop failure or failed business venture, protection, debt relief, or an appointment to some office or position in government. “Help one person with money, another with credit, another with influence, another with advice, another with sound precepts” (Seneca, Ben. ] .2.4; LCL). If the patron granted the petition, the petitioner would become the client of the patron and a potentially long-term relationship would begin. This relationship would be marked by the mutual exchange of desired goods and services, the patron being available for assistance in the future, the client doing everything in his or her power to enhance the fame and honor of the patron (publicizing the benefit and showing the patron respect), remaining loyal to the patron, and providing services whenever the opportunity arose.

The kinds of benefits exchanged between such people will be different in kind and quality, the patron providing material gifts or opportunities for advancement, the client contributing to the patron’s reputation and power base.

Aristotle speaks in his Nicomachian Ethics (1163bl-5, 12-18) of the type of friendship in which one partner receives the larger share of honor and acclamation, the other partner the larger share of material assistance – clearly a reference to personal patronage between people of unequal social status.

Moreover, because patrons were sensitive to the honor of their clients, they rarely called their clients by that name. Instead, they “‘graciously” referred to them as “friends,” even though they were far from social equals. Clients, on the whole, did not attempt to hide their junior status, referring to their patrons as “patrons” rather than as “friends” so as to highlight the honor and respect with which they esteemed their benefactors. Where we see people called “friends” or “partners,” therefore, we should suspect that we are still looking at relationships of reciprocity

Patronage and “Mediators”

Sometimes the most important gift a patron could give was access to (and influence with) another patron who actually had power over the benefit being sought. For the sake of clarity, a patron who provides access to another patron for his or her client has been called a “broker” (a classical term for this was ”’mediator”).

This is fascinating in the light of 1 Timothy 2:5, which says: “For there is one God, and one mediator also between God and men, the man Christ Jesus,”. Anyway, back to the excerpts.

Brokerage – the gift of access to another, often greater, patron – was in itself a highly valued benefit. Without such connections, the client would never have had access to what he or she desired or needed.

Reciprocity as a Social Safety Net

Great prestige is attached to a good reputation as a neighbor. Everyone would like to be in credit with everybody and those who show reluctance to lend a hand when they are asked to do so soon acquire a bad reputation which is commented on by innuendo. Those who fail to return the favor done to them come to be excluded from the system altogether. Those of good repute can be sure of compliance on all sides.

“How else do we live in security if it is not that we help each other by an exchange of good offices? It is only through the interchange of benefits that life becomes in some measure equipped and fortified against sudden disasters. Take us singly, and what are we? The prey of all creatures …. ” – Senica (Ben. 4.18.1).

The True Context and Definition of Grace

We have looked closely and at some length at the relationships and activities which mark the patron-client relationship, friendship, or public benefaction, because these are the social contexts in which the word “grace” (charis) is at home in the first century AD.

For the actual writers and readers of the New Testament, however, “grace” was not primarily a religious, as opposed to secular, word: rather it was used to speak of reciprocity among human beings and between mortals and God (or, in pagan literature, the gods). This single word encapsulated the entire ethos of the relationships we have been describing.

In Aristotle’s words “Grace (charis) may be defined as helpfulness toward someone in need, not in return for anything, nor for the advantage of the helper himself [or herself], but for that of the person helped.

In this sense, the word highlights the generosity and disposition of the patron, benefactor, or giver.

The same word carries a second sense, often being used to denote the “gift” itself, that is, the result of the giver’s beneficent feelings. Many honorary inscriptions mention the “graces” (charitas) of the benefactor as the cause for conferring public praise, emphasizing the real and received products of the benefactor’s good will toward a city or group.

Finally, “grace” can be used to speak of the response to a benefactor and his or her gifts, namely “gratitude”. Demosthenes provides a helpful window into this aspect in his De corona as he chides his audience for not responding honorably to those who have helped them in the past: “but you are so ungrateful (acharistos) and wicked by nature that, having been made free out of slavery and wealthy out of poverty by these people, you do not show gratitude (charin echeis) toward them but rather enriched yourself by taking action against them” (De corona 131).

“Grace” thus has very specific meanings for the authors and readers of the New Testament, meanings derived primarily from the use of the word in the context of the giving of benefits and the requiting of favors.

The fact that one and the same word can be used to speak of a beneficent act and the response to a beneficent act suggests implicitly what many moralists from the Greek and Roman cultures stated explicitly: “grace” must be met with “grace,” favor must always give birth to favor, gift must always be met with gratitude.

From this, and many other ancient witnesses, we learn that there is no such thing as an isolated act of “grace.” An act of favor and its manifestation (the gift) initiate a circle dance in which the recipients of favor and gifts must “return the favor,” that is, give again to the giver (both in terms of a generous disposition and in terms of some gift, whether material or otherwise). Only a gift requited is a gift well and nobly received. To fail to return favor for favor is, in effect, to break off the dance and destroy the beauty of the gracious act.

There were also clear codes of conduct for the giver as well, guidelines that sought to preserve, in theory at least, the nobility and purity of a generous act. First, ancient ethicists spoke much of the motives that should guide the benefactor or patron. Aristotle’s definition of “grace” in its first sense (the generous disposition of the giver), quoted above, underscores the fact that a giver must act not from self-interest but in the interest of the recipient. If the motive is primarily self-interest, any sense of “favor” is nullified and with it the deep feelings and obligations of gratitude (Aristotle, Nic. Eth. 1385a35-1385b3). The Jewish sage, Yeshua Ben Sira, lampoons the ungraceful giver (Sir 20: 13-16). This character gives not out the virtue of generosity but in anticipation of profit, and if the profit does not come immediately he considers his gifts to be thrown away and complains aloud about the ingratitude of the human race. Seneca also speaks censoriously of this character: “He who gives benefits imitates the gods, he who seeks a return, money-lenders” (Ben. 3.15.4).31 The point is that the giver, if he or she gives nobly, never gives with an eye to what can be gained from the gift. The giver does not give to an elderly person so as to be remembered in a will, or to an elected official with a view to getting some leverage in politics. Such people are investors, not benefactors or friends.

To whom should “Graces” (gifts/favors) Be Given?

Gifts are not to be made with a view to having some desired object given in return, but gifts were still to be made strategically. According to Cicero, good gifts badly placed are badly given (De officiis 2.62). The shared advice of Isocrates, Ben Sira, Cicero, and Seneca is that the giver should scrutinize the person to whom he or she is thinking of giving a gift.

The recipient should be a virtuous person who will honor the generosity and kindness behind the gift, who would value more the continuing relationship with the giver than any particular gift. Especially poignant is Isocrates’ advice: “Bestow your favors on the good; for a goodly treasure is a store of gratitude laid up in the heart of an honest man. If you benefit bad men, you will have the same reward as those who feed stray dogs; for these snarl alike at those who give them food and at the passing stranger; and just so base men wrong alike those who help them and those who harm them” (To Demonicus 29; LCL). An important component in deciding who will be a worthy recipient of one’s gifts is his or track record of how he or she has responded to other givers in the past. Has he or she responded nobly, with gratitude? He or she will probably be worthy of more favors. A reputation for knowing how to be grateful was, in effect, the ancient equivalent of a credit-rating.

Therefore, Seneca, would advise his readers, the human benefactor should imitate the “gods,” by whose design “the sun rises also upon the wicked” and “rains” are provided for both good and bad (Ben. 4.26.1; 4.28.1),

An image that captured this ethos for the ancients was three goddesses, the three “Graces,” dancing hand-in-hand in a circle. Seneca’s explanation of the image is most revealing:

Some would have it appear that there is one for bestowing a benefit, one for receiving it, and a third for returning it; others hold that there are three classes of benefactors – those who receive benefits, those who return them, those who receive and return them at the same time …. Why do the sisters hand in hand dance in a ring which returns upon itself? For the reason that a benefit passing in its course from hand to hand returns nevertheless to the giver; the beauty of the whole is destroyed if the course in anywhere broken, and it has most beauty if it is continuous and maintains an uninterrupted succession …. Their faces are cheerful, as are ordinarily the faces of those who bestow or receive benefits. They are young because the memory of benefits ought not to grow old. They are maidens because benefits are pure and holy and undefiled in the eyes of all; [their robes] are

The Proper Response to “Grace” I: Gratitude

As we have already seen in Seneca’s allegory of the three “Graces,” an act of favor must give rise to a response of gratitude – grace must answer grace, or else something beautiful will be defaced and turned into something ugly.

Failure to show gratitude, however, was classed as the worst of crimes, being compared to sacrilege against the gods, since the Graces were considered goddesses, and being censured as an injury against the human race, since ingratitude discourages the very generosity that was so crucial to public life and to personal aid. Seneca captures well the perilous nature of life in the first-century world and the need for firm tethers of friendship and patronage to secure one against mishap:

Ingratitude is something to be avoided in itself because there is nothing that so effectually disrupts and destroys the harmony of the human race as this vice. For how else do we live in security if it is not that we help each other by an exchange of good offices? It is only through the interchange of benefits that life becomes in some measure equipped and fortified against sudden disasters. Take us singly, and what are we? The prey of all creatures (Ben. 4.) 8.); LCL).40

Responding justly to one’s benefactors was a behavior enforced not by written laws but rather “by unwritten customs and universal practice,” with the result that a person known for gratitude would be considered praiseworthy and honorable by all, while the ingrate would be regarded as disgraceful. There was no law for the prosecution of the person who failed to requite a favor (with the interesting exception of classical Macedonia), but, Seneca affirmed, the punishment of shame and hatred by all good people would more than make up for the lack of official sanctions. Neglecting to return a kindness, forgetfulness of kindnesses already received in the past, and, most horrendous of all, repaying favor with insult or injury – these were courses of action to be avoided by an honorable person at all costs.

Practically speaking, responding with gratitude was also reinforced by the knowledge that if one has needed favors in the past, one most assuredly will still need favors and assistance in the future. As we have seen already, a reputation for gratitude is the best credit-line one can have in the ancient world, since patrons and benefactors, when selecting beneficiaries, would seek out those who knew how to be grateful.

Just as no one goes back to a merchant who has been discovered to cheat his customers, and as no one entrusts valuables to the safe-keeping of someone who has previously lost valuables entrusted to him, so “those who have insulted their benefactors will not be thought worthy of a favor (charitos axious) by anyone” (Dio, Or. 31.38,65).

As we consider gratitude, then, we are presented with something of a paradox. Just as the favor was freely bestowed, so the response must be free and uncoerced. Nonetheless, that response is at the same time necessary and unavoidable for an honorable person who wishes to be known as such (and hence the recipient of favor in the future). Gratitude is never a formal obligation: there is no advance calculation of, or agreed upon return for, the gift given. Nevertheless the recipient of a favor knows that he or she stands under the necessity of returning favor when favor has been received. The element of “exchange” must settle into the background, being dominated instead by a sense of mutual favor, of mutual good will and generosity.

Even in personal patronage (in which the parties are not on equal footing), however, public honor and testimony would comprise an important component of a grateful response. An early witness to this is Aristotle, who writes in his Nicomachian Ethics that “both parties should receive a larger share from the friendship, but not a larger share of the same thing: the superior should receive the larger share of honor, the needy one the larger share of profit; for honor is the due reward of virtue and beneficence“

Such a return, though of a very different kind, preserves the “friendship.” Seneca emphasizes the public nature of the testimony that the recipient of a patron’s gifts is to bear. Gratitude for, and pleasure at, receiving these gifts should be expressed “not merely in the hearing of the giver, but everywhere” (Ben. 2.22.1): “The greater the favour, the more earnestly must we express ourselves, resorting to such compliments as: … ‘I shall never be able to repay you my gratitude, but, at any rate, I shall not cease from declaring everywhere that I am unable to repay it‘”

These dynamics are also at work in Jewish literature with regard to formulating a proper response to God’s favors, that is, with regard to answering the Psalmist’s question “What shall I give back to the Lord for all his gifts to me?” (Ps 116: 12). The psalmist answers his own question by enumerating the public testimonies he will give to God’s fidelity and favor.

I’ll copy/paste the relevant part of the Psalm he referenced.

Psalm 116:12-14 and 17

12 What shall I render to the LORD

For all His benefits toward me?13 I shall lift up the cup of salvation

And call upon the name of the LORD.14 I shall pay my vows to the LORD,

Oh may it be in the presence of all His people.…

17 To You I shall offer a sacrifice of thanksgiving,

And call upon the name of the LORD.

The Proper Response to “Grace” II: Faithfulness

A second component of gratitude as this comes to expression in relationships of personal patronage or friendship is loyalty to the giver, that is, showing gratitude and owning one’s association with the giver even when fortunes turn and it becomes costly. Thus Seneca would write about gratitude that “if you wish to make a return for a favor, you must be willing to go into exile, or to pour forth your blood, or to undergo poverty, or, … even to let your very innocence be stained and exposed to shameful slanders”

The person who disowned or dissociated himself from a patron because of self-interest was an ingrate.

It is worth noting at this point that “faith” (Latin, fides; Greek, pistis) is a term also very much at home in patron-client and friendship relations, and had, like “grace,” a variety of meanings as the context shifted from the patron’s ” faith” to the client’s “faith.” In one sense, “faith” meant “dependability.” The patron needed to prove himself or herself reliable in providing the assistance he or she promised to grant; the client needed to “keep faith” as well, in the sense of showing loyalty and commitment to the patron and to his or her obligations of gratitude. A second meaning is the more familiar sense of “trust”: the client had to “trust” the good will and ability of the patron to whom he entrusted his need, that the latter would indeed perform what he promised, while the benefactor would also have to trust the recipients to act nobly and make a grateful response. In Seneca’s words, once a gift was given there was “no law [that can] restore you to your original estate -look only to the good faith (fidem) of the recipient” (Ben. 3.14.2).

The principal of loyalty meant that clients or friends would have to take care not to become entangles in webs of crossed loyalties. Although a person could have multiple patrons, to have as patrons two people who were enemies or rivals of one another would place one in a dangerous position, since ultimately one would have to prove loyal and grateful to one but disloyal and ungrateful to the other. “No one can serve two masters” honorably in the context of these masters being at odds with one another, but if the masters are ” friends” or bound to each other. by some other means the client should be safe in receiving favors from both.

Finally, the grateful person would look for an occasion to bestow timely gifts or services. If we have shown forth our gratitude in the hearing of the patron and borne witness to the patron’s virtue and generosity in the public halls, we have “‘repaid favor (the generous disposition of the giver) with favor (an equally gracious reception of the gift),” but for the actual gift one still “owes” an actual gift (Seneca, Ben. 2.35.1). Once again, people of similar authority and wealth (” friends”) can exchange gifts similar in kind and value; clients, on the other hand, can offer services when called upon so to do or when they see the opportunity arise. Seneca especially seeks to cultivate a certain watchfulness on the part of the one who has been “indebted,” urging him or her not to try to return the favor at the first possible moment (as if the debt weighed uncomfortably on one’s shoulders), but to return the favor in the best possible moment, the moment in which the opportunity will be real and not manufactured (Ben. 6.41.1-2). The point of the gift, in the first place, was not, after all, to obtain a return but to create a “bond” that “binds two people together” .

The Differing Rules for Patron and Client

Speaking to the giver, Seneca says that “the book-keeping is simple so much is paid out; if anything comes back, it is gain, if nothing comes back, there is no loss. I made the gift for the sake of giving” (Ben. 1.2.3). While the giver is to train his or her mind to give no thought to the return and never to think a gift “lost,” the recipient is never allowed to forget his or her obligation and the absolute necessity of making a return (Ben. 2.25.3; 3.1.1). The point is that the giver should wholly be concerned with giving for the sake of the other, while the recipient should be concerned wholly with showing gratitude to the giver.

Many other examples of this double set of rules exist. The giver is told “to make no record of the amount,” but the recipient is “to feel indebted for more than the amount” (Ben. 1.4.3); the giver should forget that the gift was given, the recipient should always remember that the gift was received (Ben. 2.10.4; see Demosthenes, De corona 269); the giver is not to mention the gift again, while the recipient is to publicize it as broadly as possible (Ben. 2.11.2).

It was within this world where many relationships would be characterized in terms of patronage and friendship, and in which the wealthy were indeed known as “benefactors” (Lk 22:25),

Biblical Examples of the Patronage System

The author gives a few examples of Patronage in the New Testament, and the two treated in the most depth are below.

Luke 7:1-10 – The Centurion’s Servant

The centurion is presented as a local benefactor, doing what benefactors frequently do – erecting a building for public use (here, a synagogue). Faced with the mortal illness of a member of his household, and made aware of Jesus’ reputation as a healer (thus himself a broker of God’s favors), he seeks assistance from Jesus whom he knows has the resources to meet the need. He does not go himself, for he is an outsider – a Gentile (and a Roman officer, at that). Instead, he looks for someone who has some connection with Jesus, someone who might be better placed in the scheme of things to secure a favor from this Jewish healer. So he calls upon those whom he has benefitted, the local Jewish elders, who will be glad for this opportunity to do him a good service (to do a favor for one who has bestowed costly favors on the community). He knows they will do their best to plead his cause, and thinks that their being of the’ same race and, in effect, extended kinship group as Jesus will make success likely. Thus the centurion’s beneficiaries return the favor by brokering access to someone who has what the centurion needs. When the Jewish elders approach Jesus, they are, in effect, asking for the favor. As mediators, they also provide testimony to the virtuous character of the man who will ultimately be the recipient of favor. Jesus agrees to the request.

The Entire Book of Philemon

Another text that prominently displays the cultural codes and dynamics of reciprocity is Paul’s letter to Philemon, which speaks of past benefits conferred by Paul and Philemon and calls for a new gift, namely freeing Onesimus to join Paul. Although Paul lacks both property and a place in a community, he nevertheless claims to be able to exercise authority over Philemon on the basis of having brought Philemon the message of salvation, thus on the basis of having given a valuable benefit (Philem 8, 18). Philemon himself has been the benefactor of the Colossian Christians, seen in his opening up of his house to them (Philem 2) and in the generosity that has been the means by which “the hearts of the saints have been refreshed” (Philem 7), perhaps including material assistance offered Paul during the time of their acquaintance and after.

We find a mixture of grounds on which Paul bases his request: on the one hand, Paul claims authority to command Philemon’s obedience as Paul’s client (Philem 8, 14, 20);61 on the other, he voices his preference to address Philemon as friend (Philem 1), co-worker, and partner, and only actually makes his request on that basis (Philem 9, 14, 17, 20), hoping now to “benefit” (Philem 20) from Philemon’s continued generosity toward the saints, which has earned him much honor in the community. The gift (really, the “return”) that Paul seeks is the company and help of Onesimus, Philemon’s slave. Paul presents Onesimus as someone who can give Paul the kind of help and service that Philemon ought to be providing Paul (Philem 13), and Paul’s mention of his own need (his age and his imprisonment, Philem 9) will both rouse Philemon ‘s feelings of friendship and desire to help as well as make failure to help a friend in such need the more reprehensible.

…

Philemon really does appear to be in a corner in this letter- Paul has left him little room to refuse his request! If he is to keep his reputation for generosity and for acting nobly in his relations of reciprocity (the public reading of the letter creates a court of reputation that will make this evaluation), he can only respond to Paul’s request in the affirmative. Only then would his generosity bring him any credit at all in the community; if he refuses and Paul must command what he now asks, Philemon will either have to break with Paul or lose Onesimus anyway without gaining any honor as a benefactor and reliable friend.

The “Aha” Moment: God’s Grace

We come at last to what is surprising about God’s grace. It is not that God gives “freely and uncoerced”: every benefactor, in theory at least, did this. God goes far beyond the high-water mark of generosity set by Seneca, which was for virtuous people to consider even giving to the ungrateful (if they had resources to spare after benefitting the virtuous). To provide some modest assistance to those who had failed to be grateful in the past would be accounted a proof of great generosity, but God shows the supreme, fullest generosity (not just what God has to spare!) toward those who are God’s enemies (not just ingrates, but those who have been actively hostile to God and God’s desires). This is an outgrowth of God’s determination to be “kind” even “toward the ungrateful [acharistous] and the wicked” (Lk 6:35). God’s selection of his enemies as beneficiaries of his most costly gift is one area in which God’s favor truly stands out.

A second aspect of God’s favor that stands out is God’s initiative in effecting reconciliation with those who have affronted God’s honor. God does not wait for the offenders to make an overture, or to offer some token acknowledging their own disgrace and shame in acting against God in the first place. Rather, God sets aside his anger in setting forth Jesus, providing an opportunity for people to come into favor and escape the consequences of having previously acted as enemies (hence the choice of “deliverance,” soteria, as a dominant image for God’s gift). We will see below that Jesus is primarily presented in terms of a mediator or “broker” of access to God’s favor, since he connects those who make themselves his clients to another patron; nevertheless, those images cannot make us ignore that even such a mediator is God’s gift to the world, hence. an evidence of God’s initiative in forming this relationship (Rom 3:22-26; 5:8; 8:3-4; 2 Cor 5:18,21; 1 Jn 4:10). The formation of this grace-relationship thus runs contrary to the normal stream of lower-echelon people seeking out brokers who can connect them with higher patrons.

The early Christians are repeatedly admonished, however, to take such a demonstration of boundless generosity as God’s single call to humankind at last to respond virtuously and wholeheartedly (most eloquently, 2 Pet 1 :3-11), and never as an excuse to offend God further (Rom 6: 1; Gal 5: 1, 13).

Grace and Prayer

Jesus did not, however, discourage prayer in spite of God’s knowledge, and the rest of the New Testament authors either promote prayer as the means to securing divine favors or display prayer as effective (e.g., Lk I:] 3). Why pray if God already knows our needs? Because God delights to grant favors to those who belong to God’s household. When we ask, we also have the opportunity to know the “blessed experience” of gratitude83 and live out our response (in fact, be ennobled by feeling grateful and responding to God’s grace). The result of the offering of prayers and God’s answering of petitions is thanksgiving “from many mouths,” the increase of God’s honor and reputation for generosity and beneficence (2 Cor]:] ]). Prayer becomes, then, the means by which believers can personally seek God’s favor, and request specific benefactions, for themselves or on behalf of one another.

Our Proper Response to God’s Grace

One of the more important contributions an awareness of the ethos of “grace” in the first-century world can make is implanting is our minds the necessary connection between receiving and responding, between “favor” and “gratitude” in its fullest sense. Because we think about the “grace” of God through the lens of sixteenth-century Protestant polemics against “earning salvation by means of pious works,” we have a difficult time hearing the New Testament’s own affirmation of the simple, yet noble and beautiful, circle of grace. God has acted generously, and Jesus has granted great and wonderful gifts. These were not earned, but “grace” is never earned in the ancient world (this, again, is not something that sets New Testament “grace” apart from everyday “grace”). Once favor has been shown and gifts conferred, however, the result must invariably be that the recipient will show gratitude, will answer “grace” with “grace.” The indicative and the imperative of the New Testament are held together by this circle of grace: we must respond generously and fully, for God has given generously and fully.

Showing gratitude to God in the first instance means proclamation of God’s favors and publicly acknowledging one’s debt to (and thus association with) Jesus, the mediator through whom we have access to God’s favor (Lk 12:8_9).103 A grateful heart is the source of evangelism and witness, which is perhaps most effectively done as we simply and honestly give God public praise for the gifts and help we have received from God. Perhaps some shrink from “evangelism” because they think they need to work the hearer through Romans, or discourse on the two natures of Christ. Begin by speaking openly, rather, about the favor God has shown you, the positive difference God’s gifts have made in your life: tell other people facing great need about the One who supplies every need generously.

This jives well with Jesus words in the Great Commission, where many people focus on the wrong things. Further, I previously wrote an article on how In Greek, the Greatest Commandment isn’t about “love”, but about obedience. The article makes a lot of sense with the next quote.

Words are not the only medium for increasing God’s honor. Jesus directed his followers to pursue a life of “good works” which would lead those seeing them to “give honor to your Father who is in heaven” (Mt 5: 16).104 As believers persist in pursuing “noble deeds,” those who now slander them will come to “glorify God” at the judgement (1 Pet 2: I1 -12).

By telling others of God’s gifts, and by being zealous for virtue and well doing. we have opportunity to advance our great Patron’s reputation in this world, possibly leading others in this way to seek to attach themselves to so good a benefactor.

Besides bringing honor to one’s patron, it was also a vital part of gratitude to show loyalty to one’s patron. Attachment to a patron could become costly, should that patron have powerful enemies. Being grateful- owning one’s association and remaining committed to that patron – could mean great loss (Seneca, Ep. 8] .27). True gratitude entails, however, setting the relationship of “grace” above considerations of what is at the moment advantageous. First-century Christians often faced, as so many international Christians in this century continue to face, choosing between loyalty to God and personal safety. For this reason, several texts underscore the positive results of enduring hostility and loss for their commitment.

Loyalty to God means being careful to avoid courting God’s enemies as potential patrons as well. In the first century, this meant not participating in rites that proclaimed one’s indebtedness to the gods whose favor non-Christians were careful to cultivate (whether the Greco-Roman pantheon or the emperor: 1 Cor 10: 14-21; Rev 14:6-13). If avoidance of such rituals meant losing the favor of one’s human patrons, this was but the cost of loyalty to the Great Patron. One could not be more concerned with the preservation of one’s economic and social well-being than living out a grateful response to the One God (Mt 6:24; Lk 12:8-9).

Clients would return gratitude in the form not only on honor and loyalty, but also in services performed for the patron. It is here that good works, acts of obedience, and the pursuit of virtue are held together inseparably with the reception of God’s favor and kindnesses. A life of obedience to Jesus’ teachings and the apostles’ admonitions – in short, a life of good works – are not offered to gain favor from God, but nevertheless they must be offered in grateful response to God. To refuse these is to refuse the Patron who gave his all for us the return He specifically requests from us. Paul well understands how full our response should be: if Jesus gave his life for us, we fall short of a fair return unless we live our lives for him (2 Cor 5:14-15; Gal 2:20).

God’s acts on our behalf become the strongest motivation for specific Christian behaviors. For example, Paul reminds the Corinthian church that, since they were ransomed for a great price, they are no longer their own masters: they owe it to their redeemer to use their bodies now as pleases him (I Cor 6: 12-20).109 In more general terms, he reminds the Roman Christians that their experience of deliverance from sin and welcome into God’s favor leaves them obliged now to use their bodies and lives to serve God, as once they served sin: they are “debtors,” not to the flesh, but to the God who delivered them and will deliver them (8: 12).”

Similarly, Paul and the author of 1 Peter speak frequently of the ways in which God has gifted individual believers for the good of the whole church. Divine endowments of this kind (whether teaching, prophetic utterance, wisdom, tongues, or even monetary contributions) become opportunities and obligations for service. The proper response to receiving such gifts is not boasting (1 Cor 4:7), which in effect suppresses the acknowledgment that these qualities stem from God’s endowment, but sharing God’s gifts with the whole church and the world. We are to exercise stewardship of the varied gifts that God has granted with the result that the honor and praise offered to God increases (1 Pet 4: 1 0-11 ).113

The Christian Scriptures also present the danger of failing to attain God’s gift (Heb 12: 15), of “receiving God’s gift in vain” (2 Cor 6: 1). Just as living out a response of gratitude assures the believer of God’s favor in the future, so responding to God’s favor with neglect, ingratitude, or even contempt threatens to make one ” fall from favor” (Gal 5:4) resulting in the danger of exclusion from future benefactions. When attempting to dissuade their audiences from a particular course of action, the New Testament authors will show the hearers how such a course of action is inconsistent with the obligations of gratitude, and how such a course threatens to tum the affronted Patron’s favor into wrath.

Conclusion

This understanding of what Grace meant to the ancient world has vastly increased my own personal understanding of the Christian life. The focus on gratitude is especially poignant, plus the focus on “repaying” God not to discharge a debt, but because it’s the only proper response to such a great gift makes so much sense to me.

It also clearly explains why the New Testament writers focus so much on our behavior and works, without making them part of how we receive God’s grace. Yet at the same time, it makes them an essential part of the Christian life. I like the duality and how it clearly lays out the proper roles for Christians in a framework that makes perfect sense.

Our proper response to God’s grace is to be grateful, faithful, and make known how great the gift that He bestowed on us was – and is.

I like that. 🙂

Hi, can you explain what is exactly it means to obey the commandment to forgive from Matthew 18? Do we have to completely ignore what someone does, only stop being angry, or release someone from the consequences of their actions? How does it apply to seeking a divorce for biblical reasons? Is unforgiveness a bigger threat to our salvation than other sins?

There is a difference between forgiveness and folly. For example, if someone steals from you, you are required to forgive that person, but you aren’t required to trust that person with money again. There’s a difference. God does this with us, for it says “the person who is faithful with little will be given much”, and also the parable of the talents. So forgiveness is mandatory, trust isn’t.

Forgiving someone also does not mean that you won’t feel hurt by what that person did. You can be hurt and still forgive someone.

As for seeking a divorce, that’s a bit different. Remember that divorce isn’t treated like most other sins, it’s treated like a crime and carries the death penalty. (See my article on divorce for details) You can forgive someone who sinned against you, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t consequences, which can include divorce if your spouses gives you proper reason. You aren’t required to divorce, but you certainly are allowed. At the bare minimum, what I said in the first paragraph of this comment applies.

As for it being “a bigger threat to our salvation than other sins“, that’s… that’s a more complicated question than I can answer in a comment. Let’s just say that willfully not forgiving someone on purpose is serious and leave it at that. (Which wouldn’t apply if you are trying to and find it hard; that’s different)

So, the gospel is that God has shown grace to us by dying for us; therefore we should share the gospel and obey because it is the proper response, and because we will be shown further grace when we are rewarded in heaven.

My main question is, does a substandard response to God’s grace result in a temporary visit to hell, or just a low status in heaven? If it’s the latter, is making an effort to repent for all sins enough, or is it required to no longer intentionally sin?

You have rather a lot of assumptions embedded in your questions so I won’t answer those, but I can give a general overview. In the sense of the afterlife, salvation is a “pass or fail” kind of thing. You can be headed for paradise and not have a lot of fruit in your life because your salvation doesn’t depend on your works. This is most clear in 1 Cor 3 where it talks about a man with poor works who will still be saved, but “as though through fire” (meaning little or no reward)

However, Jesus died not only to save us from punishment in the afterlife, but also to save us from our sins themselves. (I’m working on an article about this actually). There actually are words used in the NT that mean “intentional sin” and such sins are never treated lightly. As Paul says in Romans: “shall we continue in sin so grace may abound? May it never be!” If someone says: “it’s okay for me to sin because God will forgive me“, he has an explicitly anti-biblical mindset about sin. The right and proper response to God’s grace is obedience, as you pointed out, which includes turning from sin. We all still fail, but we should try to lead lives that are as sin-free as possible.

So, I have a lot of questions.

Is there anyway to know that you are saved?

Is repentance a work?

Will many people go to hell for sins they are ignorant of? (Female pastors, failing to submit their husband, practicing Catholicism)

Does having the Holy Spirit prove salvation?

Should a passage like 1 cor 6:9-10 be taken literally, meaning anyone who does these things is not saved?

Does 1 John 2 teach that near perfect obedience is required for salvation

Taking your questions in order:

“Is there anyway to know that you are saved?” Romans 10:9- answers this handily:

“Is repentance a work?” No. The Greek word we translate repentance literally means to “think differently after”. The idea is that you agree with God that what you did was wrong. Now, the assumption is that a change of mind will also produce a change of behavior, but repentance itself is more about agreeing with God that your sin was indeed wrong.

“Will many people go to hell for sins they are ignorant of? (Female pastors, failing to submit their husband, practicing Catholicism)“. That’s a bit stickier and it does depend on the specific sin in view. Leviticus 5:17 and Matthew 7:15-23 make it clear that it’s possible, however, Luke 12:47-48 lends some clarity to this:

Thus, ignorance is only a partial shield, not a total shield. I’m not sure exactly how this works itself out and thankfully I don’t need to be the judge.

“Does having the Holy Spirit prove salvation?” Yes, but… Okay, Bible verses first:

However, I know some people who claim to be led by the Spirit who are blatantly violating God’s commands while thinking that they are honoring Him, and of course you can’t be sure about another person.

“Should a passage like 1 cor 6:9-10 be taken literally, meaning anyone who does these things is not saved?” I would take it that way, but you should always read this in context with verse 11 to avoid misunderstanding the verse. The next verse I’ll quote is important as well.

“Does 1 John 2 teach that near perfect obedience is required for salvation” No. 🙂 Again, this must be read in context with at least 1 John 1:9, which reads:

It’s generally a good idea to read these passages in context to avoid missing things. I suggest you read my recent article: The Biggest Mistakes Most People Make When Studying the Bible because I talk more about context and how important it is in that article.